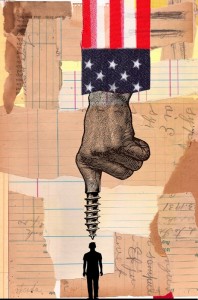

Think you’re part of the 99 percent? You may be wrong.

Half of the top one percent of earners, don’t think they’re part of that category, a new survey from wealth marketing firm, HNW Inc., finds. The survey, which polled 100 people making more than $350,000 per year, also found that two-thirds of the respondents don’t sympathize with the Occupy Movement.

That could be because many of the survey respondents’ views are at odds with those of the protesters. Nearly 45 percent of respondents said they think they pay too much in taxes and only 37 percent think the wealthy should pay more in taxes. Still, more than half of respondents said they think the financial industry needs more regulation.

Two-thirds of those surveyed also said they believe Occupy Wall Street is a “flash in the pan” - an assessment the protesters are attempting to defy even after New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg ordered police to clear Zuccotti Park of protesters and their belongings early Thursday morning. The majority of New Yorkers believe the protesters should be allowed to stay in the park, according to a Siena College poll released Tuesday.

Still, some one-percenters are throwing their weight behind the 99 percent movement. Fifty sevenmembers of Congress fall into the top 1 percent of earners, according to a USA Today analysis, including former Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi, who has said she supports the Occupy movement. In addition, celebrity one-percenters such as filmmaker Michael Moore, actor Alec Baldwin and hip-hop mogul Russell Simmons have also publicly backed the protests.

Though nearly two-thirds of the survey respondents said they believe there is a wealth gap in the U.S. - one of the many rallying cries of the movement — only 25 percent see it as a problem. That could be because it’s the rich that have been the primary beneficiaries. The one percent saw their incomes rise 275 percent between 1979 and 2007, according to the Congressional Budget Office, while Americans in the bottom fifth of earners saw an income boost of only 20 percent.

Even if all of the one percent realize they’re rich, their kids probably won’t find out. One-third of parents worth $20 million or more discussed their wealth with their children, according to a survey released earlier this month.

Source: https://www.huffingtonpost.com/2011/11/15/one-percenters_n_1095837.html

sending...

sending...