Originally posted on bbc.co.uk, August 20, 2012

Fifteen-year-old high school student Jack Andraka likes to kayak and watch the US television show Glee.

And when time permits, he also likes to do advanced research in one of the most respected cancer laboratories in the world.

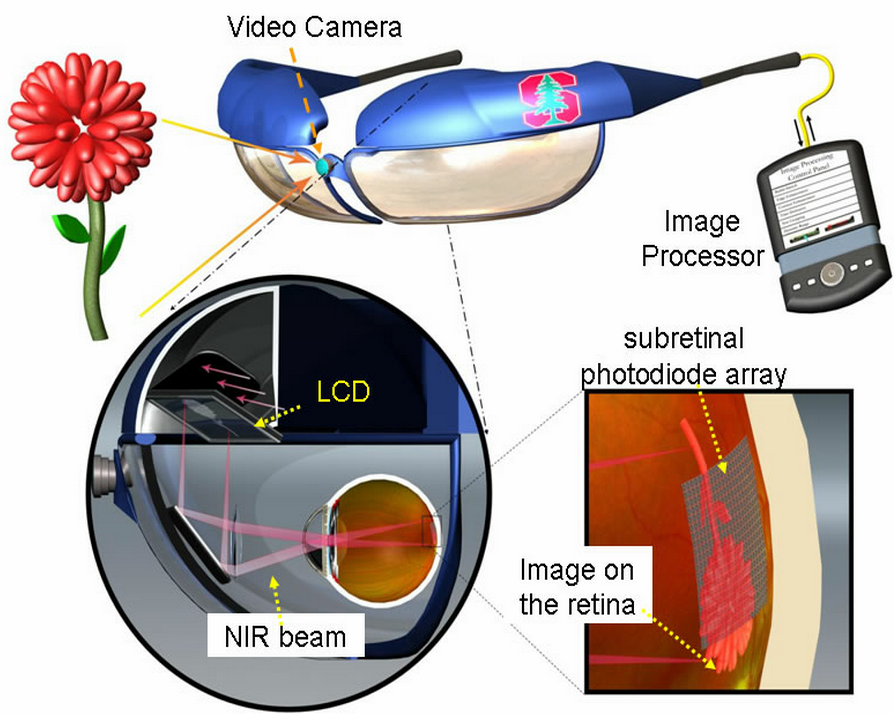

Jack Andraka has created a pancreatic cancer test that is 168 times faster and considerably cheaper than the gold standard in the field. He has applied for a patent for his test and is now carrying out further research at Johns Hopkins University in the US city of Baltimore.

And he did it by using Google.

The Maryland native, who won $75,000 at the Intel International Science and Engineering Fair in May for his creation, cites search engines and free online science papers as the tools that allowed him to create the test.

The BBC’s Matt Danzico sat down with the teenager, who said the idea came to him when he was “chilling out in biology class”.

sending...

sending...