In my life, feminism is everywhere and nowhere. I am mother to an 8-year-old son and 3-year-old daughter. The night my daughter was born (at home with a midwife, for those who care about that sort of thing), I spent the entire time obsessing over whether I was a good enough feminist to mother a daughter, instead of basking in the hormone high of new love.

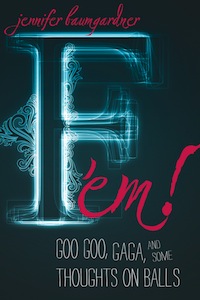

“Our job today is less to kick open doors and more to walk into rooms.” So says Jennifer Baumgardner in her new book of feminist essays, “F ’em! Goo Goo, Gaga, and Some Thoughts on Balls.”

As a stay-at-home mother, work-from-home writer, part-time teacher/performer/curator, I understand Baumgardner’s words. I worried that choices I’d made would somehow set my daughter back—that she wouldn’t have a role model. I struggled with the demands of raising a family and needing health insurance while my husband made more money and I was exclusively breastfeeding. This was not the idea I had of myself as a feminist.

Baumgardner gives us her core ideas of feminism: “Egalitarianism, eradicating sexism and recognizing the historic oppression of women. Feminism is the belief in the full political, social and economic equality of all people. Feminism is also a movement to make sure that all people have access to enough information and resources (money, social support) to make authentic decisions about their lives. Thus it’s not the decision one makes so much as the ability to make a decision.” She explains that the feminism she practiced was an “expression of the trends that shaped [her] youth.”

Baumgardner’s first essay is “The Third Wave Is 40.” It opens with a neurotic moment about the author’s look

F ’em! Goo Goo, Gaga, and Some Thoughts on Balls

By Jennifer Baumgardner

Really? This is a book about feminism and you open with your looks?

I mean, I get it. I just turned 40 and I’m losing my looks too. I’m a feminist who is also mourning the loss of being an object, however retro and unenlightened that may sound. It’s part of what lies underneath the loss of Baumgardner’s identity as a “young feminist.”

She does admit to “a certain dissonance in my attempt to be a good actualized feminist and my desire to get the love and sexual attention I wanted.” And it is Baumgardner’s unflinching willingness to explore territory like this that makes “F ’em!” such an exciting read.

I love how Baumgardner connects her (my) generation with the feminists of the ’70s and also the women younger than we are. She puts ’90s feminism in as much of a historical perspective as possible, given that it was so recent.

An important theme of “F em!” is the existence of Third Wave feminism. The First Wave (1840-1920) focused on the rights of citizenship. The Second Wave (1960-1988) “fought for women to share in the opportunities and responsibilities men had, including creating a career, pushing off the drudgery of housework and refusing to be held hostage by their reproductive systems.” The Third Wave, which Baumgardner identifies with, was approximately 1988-2010: “Whether or not these individual men and women were raised by self-described feminists—or called themselves feminists—they were living feminist lives: Females were playing sports and running marathons, taking charge of their sex lives, being educated in greater numbers than men, running for office and working outside the home.” The most recent wave, the Fourth, approximately 2008 and onward, continues the legacy of the Third Wave and moves it into the tech-savvy, gender-sophisticated world of blogs, Twitter campaigns, transgenderism, male feminists, sex work and complex relationships within the media.

I understand why Second Wavers, who lobbied for Roe v. Wade, Title IX and the Equal Pay Act, see the Third Wavers as frivolous in our lipstick and lace T-shirts. We wore no bluestockings or even redstockings—just fishnets. And there were holes in our argument too—that taking control of our sexuality was powerful. Current TV shows like “Two Broke Girls” and “Up All Night” get a lot of credit for being female-driven, supposedly showing feminism in action, and while I personally find them enjoyable, it’s more for the liberal sprinkling of vagina jokes than anything else. I can see why some Second Wavers would be mad at us. Baumgardner writes of Second Wavers, “They were no longer the ones needing abortions or utilizing current technology.” Ouch. They fought so hard to get us out of the kitchen for this?

Competition between women, and the exclusion and rage that accompanies it, is a theme throughout “F ’em!.” Female competition is used to keep women down, and surely those who are oppressed oppress others, right? Baumgardner acknowledges this: “There is a sense that mentoring and torch passing steal from one’s own hard-won store of power.” I would have loved a more overt study of female competition.

“Every few years, feminism gets kicked up to marquee status under the rubric of having failed, like a stain remover that just didn’t do its job.” So starts an essay about the divides feminism has succumbed to—black/white, gay/straight, pro sex/anti porn—and, more specifically, about Ariel Levy’s 2005 work “Female Chauvinist Pigs,” which accused Third Wave feminists like Baumgardner of “making sex objects of other women and of themselves.” The writing is lively and fun and Baumgardner’s epilogue is what’s interesting here: She recounts meeting Levy for a drink “over the warm buzz of cocktails on a wintry Manhattan night” and liking her, noticing what they had in common. Baumgardner’s willingness to look back on her own work and show us how her positions have changed or matured is just one of the generous gifts she has to offer.

One of my favorite pieces in this collection is “Womyn’s Music 101,” which should be required reading for any cultural feminist. And certainly for any woman who makes music. This piece connects activism and art, giving us a history of women’s music in the ’60s and ’70s. It chronicles the beginnings of “lesbionic” Olivia Records (I was so happy Baumgardner used that word!) and Ladyslipper, which were around long before Lilith Fair. I had never heard of Cris Williamson before, nor did I know that the lesbian cruise line Olivia had begun as Olivia Records. She draws lines between Williamson in 1973 and Riot Grrrl in 1992.

The impact of “women’s music” is still reverberating today. But remember—for those of you who were around—when there were weird strong women in rock? When Courtney Love was cool in 1994? My friend Cat and I would make an open fist with an “O” and punch the air repeatedly whenever a Hole song came on in a bar.

Source: http://www.truthdig.com/arts_culture/page2/the_evolution_of_feminism_20111208/

sending...

sending...